The tragic, factual history of Scotland's horrifying witchhunts is now revealed, as well as why the victims of these heinous murders must always be remembered.

Efforts are underway to offer pardons and apologies to the thousands of people slaughtered during Scotland's 'Satanic Panic,' which peaked in the 1600s.

Professor Julian Goodare, Scotland's preeminent witchcraft historian, chats with our Writer at Large Neil Mackay to learn more about what occurred and why we should remember these heinous crimes.

If a campaign led by the organization Witches of Scotland succeeds, some of the region's most maligned people may be forgiven.

Gary Knight, proprietor of History and Horror Tours in Blackford, is fascinated by the darker side of history.

Gary is aware with several other incidents of local residents being charged with witchcraft and condemned to death under the Witchcraft Act, which was in effect from 1563 until 1735.

"There is a request to pardon over 4000 people, according to some estimates, who were detained, tortured, and compelled to confess before being brutally killed," he stated.

Strathearn was not spared from the mayhem.

"I won't argue whether Maggie Walls was a real person or not.

I won't address our most famous instance of Kate McNiven, who was burnt to the north of Knock Hill in 1615 — there are some contradictory dates as to the date of Kate's execution.

"There are other unfortunate victims who need to be recognized as well."

Violet Mar, who resided near Muthill, was one of the first people to be accused of witchcraft under the Witchcraft Act.

“ Violet appeared in front of local landowners accused of employing witchcraft against the Earl of Mar in 1577.

There seems to be no record of Violet's fate, although she admitted that things did not appear to be going well for her.

"Another is The Warlock of the Kirkton in Auchterarder," Gary said.

This case is unique in that it concerned a man named Alexander Drummond who was tried in 1629.

Alexander had been under the church's cautious observation as he utilized his talent to heal humans and animals.

"He cured 'all sorts of diseases by sorcerie and witchcraft, and ane consulter with the devill and seiker of responses from him; havin also ane familiar spreit attending him to give him instructions in the practeis of all his diabolical and unlauchfull cures,"

according to the charges leveled against Alexander.

Alexander was sent to Edinburgh, where he was tried and killed on the city's Market Cross.

"Dunning had some convicted witches sentenced to death; in Perth, witches were burned on the North Inch."

John Mcllvorie stood before four commissioners in Crieff after being implicated by another person accused of Witchcraft – it seems John was also a healer and had attended witches meetings or Sabbaths in 1643.

In 1662, the Crook of Devon had a widespread witchcraft panic.

Agnes Murrie, Bessie Henderson, Isabella Rutherford, Robert Wilson, Bessie Neil, Margaret Lister, Janet Paton, Agnes Brugh, "At the time, the Laird of Tullibole and his son were present at these people's trial.

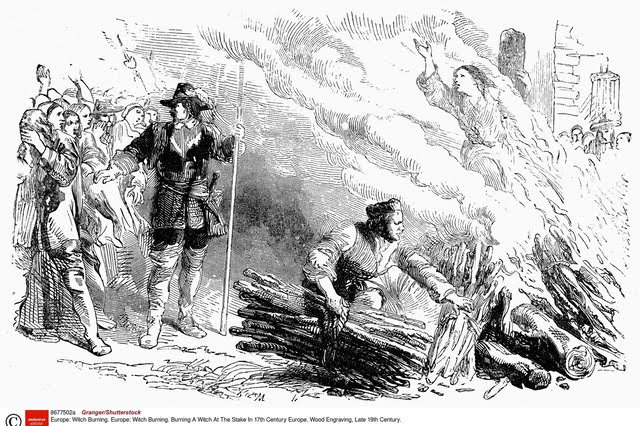

When they were found guilty, they were strangled and burned by a common hangman.

The present owners of Tullibole Castle planted a labyrinth with 11 stones in 2003 as a tribute to the victims of this heinous crime.

"Access to this laudable attempt to commemorate and apologize for one of our darkest eras in history is unfettered and free to everybody," they said.

In a superstitious and prejudiced age, a formal pardon for those accused of witchcraft is long overdue, in my view."

We are pleading with the Scottish Government to help right what we regard as Scotland's historical wrongs, and we are trying to get legal pardons and public apologies for the estimated 3837 persons accused as witches, two-thirds of whom were hanged and burnt.

And, if successful, it may mean justice for people like nursemaid Kate McNiven, who was condemned to death by strangulation and burning on the Knock of Crieff, and Maggie Wall or Walls, a Dunning witch who was the subject of one of Scotland's earliest witch monuments.

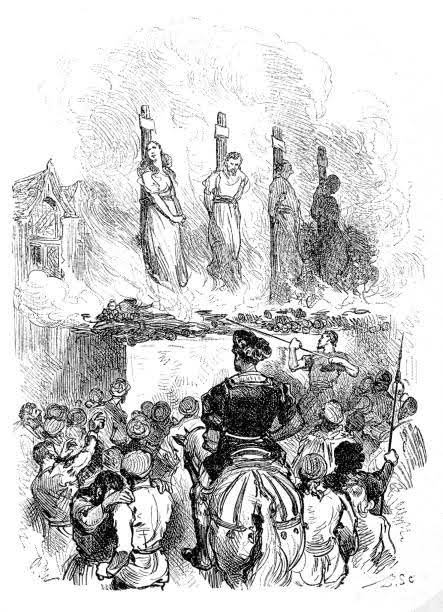

A discussion is raging in Scottish culture – like a mystical potion simmering in a burning cauldron – about how we come to terms with one of our country's worst chapters: the execution of around 2,500 individuals, primarily women but some males, as witches.

Claire Mitchell and Zoe Venditozzi are pushing for pardons for all individuals imprisoned in Scotland for witchcraft, the great majority of whom were women, as well as a monument to those who have been forgotten by history.

"Approximately 4,000 individuals were accused of witchcraft in Scotland between the 16th and 18th centuries," said Mitchell, a lawyer who formed the advocacy organization Witches of Scotland.

In all, almost 2,500 persons were killed in Scotland for witchcraft, with four-fifths of them being women.

After making confessions that were typically extracted under torture, they were generally strangled and then burnt.

"People would take turns interviewing them, keeping them awake for days and days and She went on to say that the victims were made to admit that "they were dancing with the devil, having sex with the demon."

"And the Scottish courts exploited such admissions to punish these women for witchcraft."

A tiny column dubbed the "Witches' Stone" marks their location in the wind-blown 16th-century graveyard.

Flowers and cash are often left by passers-by as a homage to individuals who have been killed, including Grissel Jaffray, who was strangled and burned in 1669.

A mosaic representing a cone of flames on a city center roadway honors Jaffray, the lady regarded as "Dundee's last witch."

Mitchell formed Witches of Scotland on March 8, 2020, International Women's Rights Day, after learning about the horrors of the Witchcraft Act.

This legislation, which was in effect until 1736, allowed the death penalty for persons found guilty of witchcraft.

Scotland's King James VI, who later became King James I of England in 1603, was a strong supporter of witch hunts.

William Shakespeare's "Scottish drama," which features three witches who lead Macbeth to his demise, gave expression to his preoccupation.

Mitchell's group wants three things: a pardon for all people convicted of witchcraft, an official apology from the government, and a national memorial to the victims.

Despite growing up in Fife, a hotspot of executions, co-campaigner Zoe Venditozzi, 46, claimed she knew "nothing" about the witch hunts until lately.

She noticed that "anyone may be implicated," and that those who couldn't speak up for themselves or were seen as unusual in some manner were "usually regular people, typically impoverished people."

"Back then, people believed in the devil a lot," she claimed, adding that women were seen as "vessels" that the devil could use.

Natalie Don, a member of the Scottish National Party, the pro-independence party in power in Edinburgh, plans to present a bill in the Scottish Parliament to grant all individuals convicted a pardon.

"People are still convicted and punished for practicing witchcraft in various nations throughout the globe" .

"Scotland should take the lead in recognizing the atrocities of our past and ensuring that these individuals are not remembered as criminals."

According to Julian Goodare, retired professor of history at Edinburgh University, who has supervised the construction of a database to chronicle witch hunts, Scotland was especially prone to them.

He claimed at Edinburgh Castle, the site of numerous public executions, that the rate was roughly five times greater than the European norm, with 2,500 people hanged in a population of two million.

Scotland's movement away from the Catholic Church during the Protestant Reformation, which witnessed widespread "fear of ungodliness," exacerbated following an alleged plan to bewitch King James in the 1590s.

"There's nothing we can do to undo the past, but we can learn from it," he says of a memorial commemorating this history.

According to a historian, women who were labeled witches and murdered in Scotland over 300 years ago had Lymes disease.

Dr. Mary Drymon, a US professor, believes people suspected of possessing the Devil's mark were most likely bitten by a tick.

It comes as Nicola Sturgeon plans to pardon hundreds of people convicted of witchcraft between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.

The Witchcraft Act was passed in 1563 and stayed in effect until 1736.

The First Minister has backed a members bill introduced by Natalie Don MSP, and when it is enacted next year, she is likely to deliver a public apology.

"I have looked at the concept of the Devil's mark and the Witches teat, as it is described in the literature," Dr. Drymon, 70, said.

The Devil's mark seems to be the bull's eye rash of Lyme disease, while the witch's teat appears to be lymphocytoma, which may develop after a tick bite.

People have reported discovering pins lodged in their flesh that magically vanish over time.

After a bloodmeal, an attached tick that looks like the head of a handcrafted 17th century brooch slips off." The lecturer believes Anne of Denmark's perilous sea journey to Scotland prior to their marriage triggered King James VI's obsession with witches.

"I believe that the level of Lyme disease in Scotland ebbed and flowed dependent on land usage and climate, notably during King James' reign and after his bride's arduous sea trip provoked his acute witch obsession," Dr. Drymon stated.

The Little Ice Age brought not just cold, but also damp and dry weather, crop failures, and famines.

Droughts tend to concentrate ticks along streams and rivers in rural regions, where sheep, deer, and mice drink water.

"Those are the locations at most risk for Lyme infection—in the past and now."

"The Scottish idea to pardon suspected witches is helpful because it sheds focus on a tremendous historic injustice," she continued.

Claire Mitchell QC and teacher and writer Zoe Venditozzi, who manage the Witches of Scotland Campaign, want the Scottish Government to offer a formal apology to all people who were convicted as witches and for an official apology to be made.

Women made up 84 percent of the victims, who were strangled before being burnt at the stake.

Mitchell and Venditozzi have both been invited to the petitions committee of the Scottish Parliament.

"This is a fascinating concept and not one I've heard before," remarked Miss Venditozzi, 46.

Some of the examples could make sense, but we also know that many of the so-called "witch's markings" might be as random as a birthmark, scar, or mole.

"I knew there was a perception that looking for marks was scientific, and that it was a source of income for certain individuals."

The petitions committee is in charge of the campaign. They want to hear from me and Claire.

When it came to witch-hunting, Scotland was the most ruthless country in Europe, murdering considerably more individuals per capita than any other country.

Today, apologies and tributes for those who died are being discussed.

With legislation to pardon victims, the Scottish Government seems to be on track to confront this legacy of the past.

Catalonia has just pardoned people who were killed as witches centuries ago.

But, beyond the facts, what do we in Scotland actually know about this horrible period of our history?

The actual narrative of the Scottish witch hunts is much more incredible than we imagined, shattering conventional beliefs and demonstrating that much of what we believe to be true is just fiction.

We contemporary Scots, like our religious forefathers, are perplexed by witches in certain ways.

Professor Julian Goodare of Edinburgh University has been tapped by The Herald on Sunday to uncover the truth about what happened in the 16th, 17th, and even early 18th centuries.

He is the director of the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft and the author of Scottish Witches And Witch-Hunters, Witchcraft And Belief In Early Modern Scotland, and The European Witch-Hunt, all of which are about the "Satanic Panic" that engulfed the nation from the end of the 1500s.

SURPRISINGLY, there was no "craze" for witch-hunting throughout the Middle Ages, or medieval era.

The hunts did not truly take off until the late-16th and early-17th centuries (far into what historians refer to as the early modern era).

However, the medieval period laid the groundwork for future persecution.

Several heresies erupted in Europe during the 1400s, including the Lollards in England and the Hussites in Bohemia, both of whom attacked the Catholic Church.

As a result, "there's a lot of fear about heresy and heretics" on the increase throughout the Middle Ages, according to Goodare.

Then there's Luther and the Protestant Reformation, which focuses on adhering to the Bible's teachings to the letter.

Anyone caught behaving in a way that contradicts the Bible might face harsh consequences.

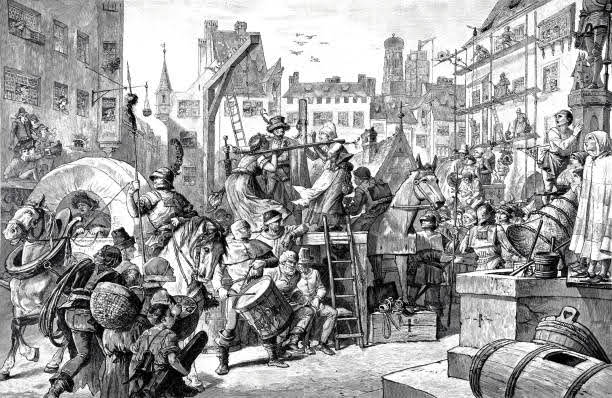

Importantly, the witch hunts coincided with a "growth in state authority – and religion was part of that political power," according to Goodare.

As European culture progressed, there was simply "more government," and rulers' decisions were based on the Bible.

As a result, the reformation and "big government" clashed, resulting in a situation in which "state officials were seeking to show they were holy... This is where hysteria may arise.

If you drew a graph depicting the increase of witch-hunting and the rise of governmental authority, they'd be nearly parallel." Religion was also open to the public.

Everyone was a devout Christian, and if you strayed from the path, "you'd be in trouble."

The Kirk Session in Scotland was in charge of maintaining control, and it could summon parishioners for interrogation and punishment for "fornication" or "breaching the sabbath," with punishments included modest fines and public shame.

Goodare notes that accusing persons of witchcraft was "far unusual."

The Kirk Session, on the other hand, was primarily responsible for initiating witch trials, since it was administered by local ministers and elders, most of whom were affluent tenant farmers.

"They are the ones who acquire the first data."

They might question the subject or gain information from their surroundings."

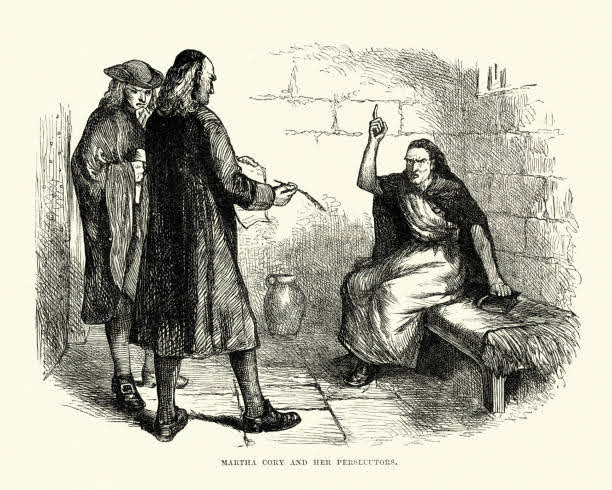

Torture was utilized as well.

When the Kirk deemed someone to be a witch, the accused was sent to "secular criminal tribunals."

The "village witch" and the "demonic witch" are the two categories of witches attacked, according to GOODARE.

He explains, "The village witch is someone who is supposed to have charmed their neighbors."

The village witch is generally caught in a situation like this: two neighbors fight, insults and threats are exchanged, and one of the neighbors' cows or even their kid dies as a result.

Suspicion falls on their "adversary" as a witch right away.

"There are a lot of instances like that in witchcraft trial records," Goodare explains.

This cause and effect equation made perfect sense to the typical person in the 1600s: Person X despises Person Y; something horrible occurs to Person Y; thus, Person X must be a witch.

The authorities were more interested in the demonic witch — "someone who has struck a contract with the Devil."

The famed North Berwick witches, suspected of scheming with Satan to assassinate King James VI of Scotland, subsequently James I of England, are a notable example.

It was a phenomenon in 1590, and it fueled the witch hunt.

The episode is said to have influenced Shakespeare's creation of the witches in Macbeth, a play written for James, who was interested by the subject.

When someone was accused of being a village witch, it was quite simple for the case to escalate into the much more severe charge of being a demonic witch.

If someone is brought before the Kirk for bewitchment, the authorities will investigate if the accused is involved in anything more hazardous, such as collaborating with the Devil.

As a result, questions are asked, and torture is utilized...

Inevitably, convicts admit to having met Satan.

To appreciate how scary the thought of a Satanic alliance may be, Goodare suggests seeing ourselves in the shoes of a typical 16th-century peasant.

They were adamant about demons, and the idea of other humans cooperating with the Devil was a "horrific prospect" for them.

In the Middle Ages, there was no such dread of a "subversive plot in collaboration with the Devil." However, as this new concept gained traction, it quickly devolved into widespread terror.

In 1597, King James wrote a book called Daemonologie.

Consider what would happen if a politician today authored a best-selling book identifying a "enemy within," and what the consequences would be.

It was said that witches were murdering and consuming newborns.

Goodare compares the "Satanic Panic" of the 1980s, when false charges of persons engaging in ritual child abuse were made all across the globe.

But, as Goodare points out, the witch-hunters were "sincere, not cynical" — they weren't fabricating accusations, and they really felt they were battling evil.

Many victims are thought to have been unjustly implicated by their opponents on purpose.

What better way to humiliate a competitor than by accusing them of witchcraft?

That concept, however, does not hold up under investigation, according to Goodare.

Persons who accused others of being witches thought the people they were accusing were in cahoots with Satan or doing black magic.

There has also been a long-held conviction that many of the victims were practicing pagans rather than devil-worshippers, and that religious authorities mistook one for the other at the time.

According to Goodare, this is not the case.

"The notion that these individuals were knowingly heathen has no foundation in fact." They all pretended to be Christians."

"You do find folks who, despite the fact that they claim to be Christians, do what I'd call'magic,'" he says.

These are what we may refer to as "folk healers." People like that can be found in most traditional European civilizations in the early modern era." Ironically, the charms they made would often include petitions to God.

These healing practices were not a big deal in the Middle Ages, but after the Reformation in the late 1500s, "the people trying to clean up Christianity were going, 'wait a minute, the Bible doesn't tell you to do that, this is wrong.'"

GOODARE believes that greater research by psychologists and historians into the mental states of both accusers and accused during the witch hunts is needed.

Although he claims that he doesn't detect proof of autism in court records, he thinks that autistic persons may confess to crimes they didn't commit.

However, it is hard to verify this in hindsight.

Some of the accusers may have had additional mental health issues.

Mental illness is linked to obsessive-compulsive behavior.

Christian Shaw, a rich 10-year-old girl from Renfrewshire, was stated to be "vomiting coal and bent pins" in 1697.

Seven individuals were hanged for allegedly bewitching her.

"There's quite apparent psychopathology of some type surrounding Christian Shaw," Goodare adds.

Janet Douglas, a little girl who was a part of Glasgow's "Pollock Panic" in the 1670s, displayed evidence of "what professional psychologists today would label catatonic mutism," according to Goodare.

According to Goodare, the most plausible choice for a disorder that afflicted both the accusers and the accused is sleep paralysis.

It may lead to delusions and out-of-body experiences.

It was called "hag-ridden" in the 1600s, as if your sleeping body had been possessed by a witch.

Accused witches have claimed that the Devil visited them while they were sleeping.

THERE IS a definite link between this and the present occurrence of persons claiming to have been visited by aliens in their beds.

According to Goodare, people may "understand sleep paralysis in cultural terms." So, someone who now legitimately thinks they have been abducted by aliens may have thought they were meeting Satan 400 years ago.

In all cases, however, the cause was just sleep paralysis.

When asked whether they encountered the Devil, some individuals declare, "Well, I didn't meet the Devil, but I did meet the Queen of the Fairies," according to Goodare.

According to Goodare, these folks seemed to think they had encountered fairies.

He explains, "It sends us back to hallucinations."

"Some folks are experiencing hallucinations today and claiming to have been kidnapped inside spacecraft."

I see nobody in the 17th century say ‘I was whisked away in a spaceship’ but I do see people claim they were transported to fairyland.”

The difficulty was that if these folks who honestly felt they had encountered fairies – either because of sleep paralysis or some other ailment – made such statements to their interrogators they were still digging their own graves.

Meeting fairies rather than demons wouldn't assist them with witch-hunters who believed fairies were merely devils in disguise, according to Goodare.

Witch-hunting was "primarily a lowland phenomena," according to the author.

In the Scottish Highlands, it doesn't have much momentum, and only a few Gaelic speakers are hanged for witchcraft." There's a suggestion that the witch hunts would have been even more vicious if Gaelic-speaking areas didn't believe in fairies.

Interestingly, Gaels attributed poor luck to fairies rather than neighbors accused of witchcraft.

"That might effectively eliminate hunting before it occurs," adds Goodare.

In Gaelic communities, the protestant church, with its Kirk Session and reforming zeal that spilled over into witch-hunting, "doesn't have traction on the ground."

WOMEN MADE UP APPROXIMATELY 85% OF VICTIMS IN SCOTLAND, WHICH COMPARED TO APPROXIMATELY 80% IN EUROPE.

Women have suffered the brunt of persecution for a variety of reasons.

For starters, society assumed that witchcraft was more likely to be committed by women.

If men were to do evil, they would do it by acts of violence rather than curses.

"The perception was that women would utilize shady tactics," Goodare adds.

The Margaret Barclay case from 1618 in Irvine is a good example.

Barclay had a sour relationship with a local sea captain who had slandered her.

"She walks out to the quayside in front of everyone and points her finger at him," Goodare recounts, pleading with God to "let the crabs devour him." The ship sinks, which is unfortunate for Barclay.

"All it took was for her to be identified as a witch and executed." As the hysteria increased, more people were implicated and burnt.

"These are the kinds of encounters that happen in a community on a daily basis." Goodare compares the bigoted belief that women were more likely to be witches to current events, in which ethnic minorities are more likely to be frisked by police.

Women, on the other hand, were more likely to accuse other women.

Women were involved in many "village-level quarrels." So this isn't just a case of guys belittling women.

It's just as probable that a woman would protest, claiming that "someone else enchanted me."

Although it may be uncomfortable to comprehend now, most women in this time sought to "conform to patriarchal standards."

"Trying to seem like a nice, married lady, nourishing your family, and defending your family from magical assault – and that means women will regard other women as witches," she said.

"Witchcraft separates women," Goodacre says.

WHY were the witch hunts in Scotland particularly harsh in comparison to the rest of the world?

The witch hunts in Scotland lasted from 1563 until 1736, when the Scottish Witchcraft Act was repealed.

In a population of around one million people, over 2,500 individuals were burnt as a result of roughly 4,000 charges.

"My gut impression is that number is too low, and the true amount is likely to be higher," Goodare adds.

In European terms, Scotland ranks nearly five times higher than the norm.

If Scotland hanged the normal amount of people, it would result in roughly 500 deaths - I regard this as a measure of the reformation's vigor."

Simply said, Scotland was more fanatical, and as a result, more prone to panic and witch-hunting.

Consider how, while protestant reformers in England were unable to "ban" Christmas, the Kirk was able to do so in Scotland, demonstrating the Kirk's power.

"A contributory factor" was also King James.

His book Daemonologie (which he coined) "draws attention to the entire phenomenon."

He gets things started, gives them legitimacy, politicizes them, and makes it acceptable for high-level government officials to be interested in these issues in a way that they might not have been otherwise.

The scientific revolution ushered in "new ways of thinking about the physical world," putting an end to the witch hunts.

"The fall is well under way" by the time of the Enlightenment.

The abolition of superstition was aided by scientists and philosophers such as Sir Isaac Newton and René Descartes.

"When they look at anything, they assume it's made of tangible substance.

That's cool – it's something new.

That is state-of-the-art research."

Society starts to "lost sight of the devils" whenever science takes center stage.

Likewise, the legislation changed.

"Judicial skepticism was essential," Goodare says.

Judges begin to require "the highest standards of evidence" and become "anti-torture."

Because so much of the witch hunts were focused on class – with those in authority dictating the parameters of the argument - the terror only subsided when "the elite's ideas changed."

In the 1600s, Europe had similarly bled itself white in brutal religious battles, and there was a feeling that "this has got to end." Goodare compares the shift to the post-World War II era, when the people concluded "we can't do it again."

They fled into myth, mythology, and amusement after the witch hunts were over.

Until Goodare's generation of historians came along and began examining social and cultural history, historians tended to disregard the awful atrocities that had occurred.

As a result, the big question remains: how do we remember this period of our history and lives?

Goodare is a believer in apologies and pardons.

He does, however, want a memorial to the victims of the witch hunts, similar to the one in Norway.

"I'd want to see a monument stimulate more dialogues; more people would see it, speak about it, and learn from it — that's what I'd like to see."

Understanding and reflecting on the true history of the witch hunts, according to Goodare, would be the greatest testament to those who perished.

He advises that we learn certain hard facts, such as the fact that the witch-hunters didn't do what they did "because they were bad."

They did what they did because they believed their intentions were "logical" and "good."

"I want people to ask themselves,

'Would I have done any better in their shoes?'

" I'd want people to consider how we pre-judge others and believe we're right and others aren't because we despise them, and that if we despise them, we can do anything we want to them.

Those are universal issues that haven't gone away.

If something comes up in the discussion, I won't feel like I've wasted my time."

You may also want to read more about Feminism and Activism here.